HMS Iphigenia (1804) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Imperieuse'' was a 38-gun

In December 1807, ''Imperieuse'' was given a two-month cruise in the Adriatic and seized three merchant vessels carrying illegal licences to trade. She was subsequently dispatched to the western Mediterranean in February where she sank two

In December 1807, ''Imperieuse'' was given a two-month cruise in the Adriatic and seized three merchant vessels carrying illegal licences to trade. She was subsequently dispatched to the western Mediterranean in February where she sank two

''Imperieuse'' returned to Plymouth on 19 March 1809 and was ordered to depart again just 10 days later to join Admiral Lord Gambier's blockading squadron at Basque Roads, France. A French fleet lay at anchor in the narrow roadstead and the British Admiralty sought to destroy it by means of a

''Imperieuse'' returned to Plymouth on 19 March 1809 and was ordered to depart again just 10 days later to join Admiral Lord Gambier's blockading squadron at Basque Roads, France. A French fleet lay at anchor in the narrow roadstead and the British Admiralty sought to destroy it by means of a

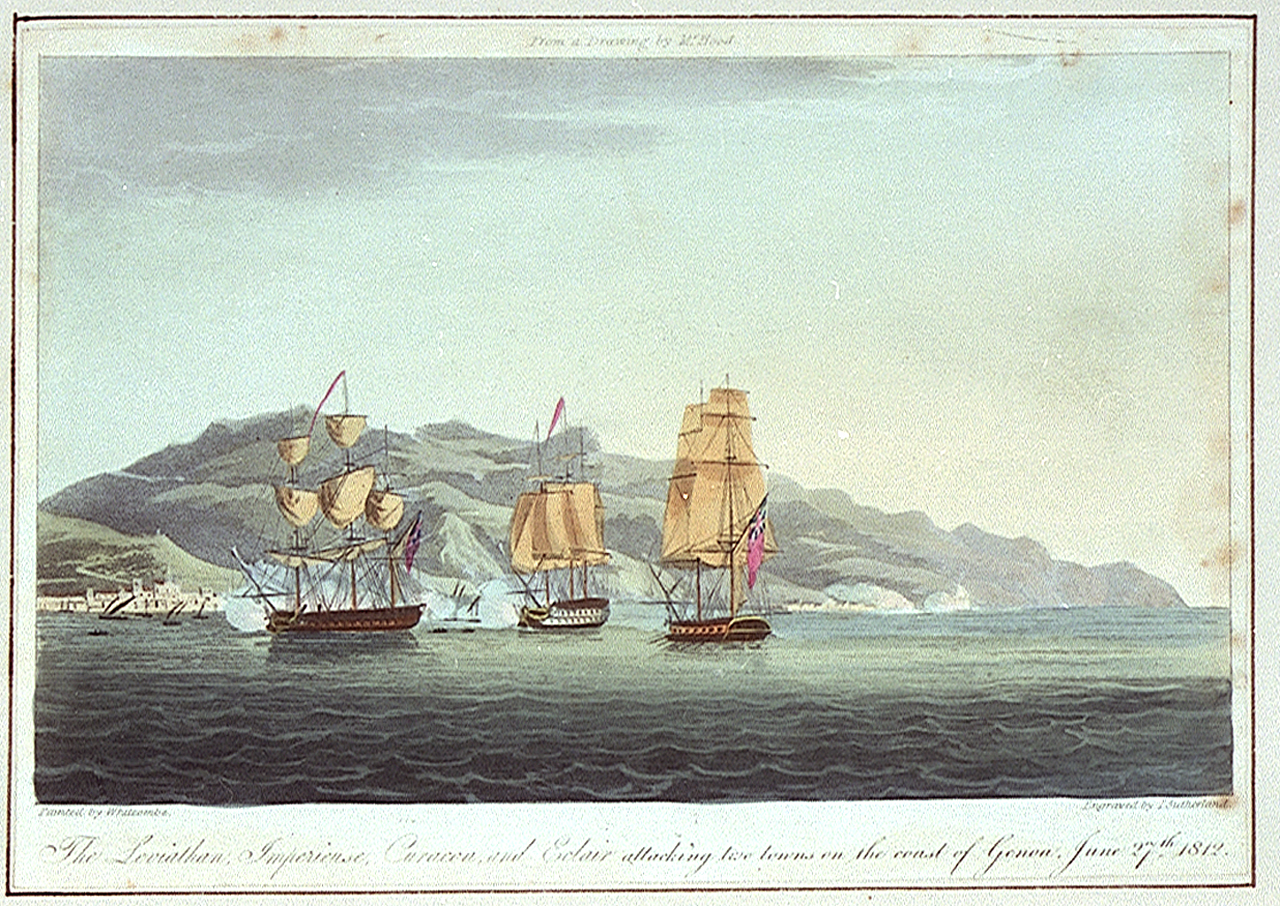

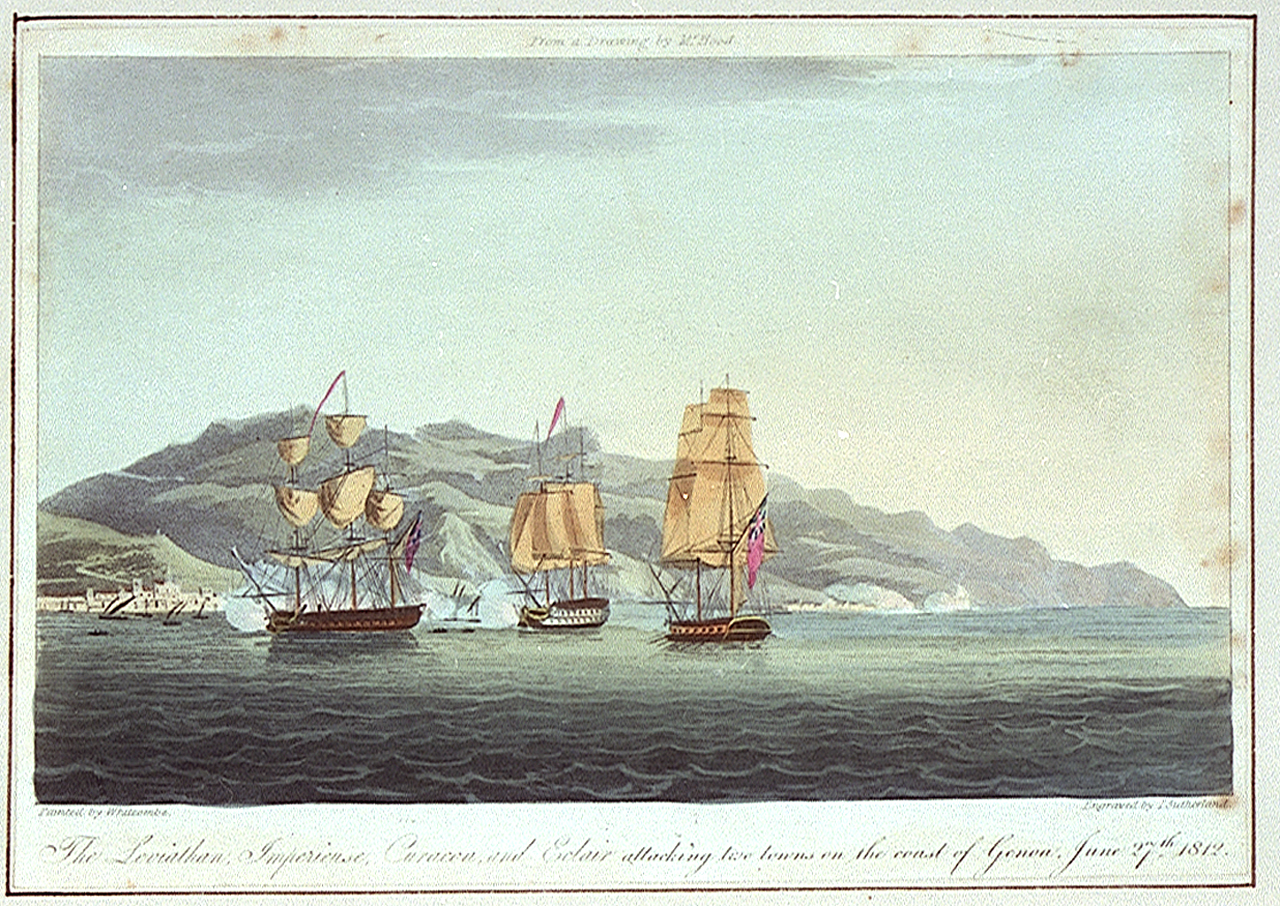

In June 1812, ''Imperieuse'' was part of a squadron commanded by Captain Patrick Campbell of the 74-gun ship of the line HMS ''Leviathan'' patrolling the western coast of Italy. On 27 June, the squadron launched boats to attack a convoy of 18 French vessels anchored off Alassio and Laigueglia. Although the British destroyed two batteries on the shore, they encountered heavy resistance from the French defenders. Attempts to bring off the French vessels were abandoned and they were instead destroyed by the British guns. While carrying out the expedition ''Imperieuse'' sustained four killed and eleven wounded.

Later that year ''Imperieuse'' returned to Port Mahon for an extensive refit and while she was undergoing repairs Duncan was offered the command of the frigates HMS ''Resistance'' and HMS ''Undaunted''. However, he decided to remain with ''Imperieuse'' after receiving a letter from the crew expressing their admiration for the captain and their desire for him to remain with the ship. In April 1813 ''Imperieuse'' departed Mahon leading a squadron of three frigates and two brigs to resume the blockade of Naples.

In September the squadron arrived off the Port of Anzio where it discovered a French convoy of 29 merchant vessels protected by two batteries on a

In June 1812, ''Imperieuse'' was part of a squadron commanded by Captain Patrick Campbell of the 74-gun ship of the line HMS ''Leviathan'' patrolling the western coast of Italy. On 27 June, the squadron launched boats to attack a convoy of 18 French vessels anchored off Alassio and Laigueglia. Although the British destroyed two batteries on the shore, they encountered heavy resistance from the French defenders. Attempts to bring off the French vessels were abandoned and they were instead destroyed by the British guns. While carrying out the expedition ''Imperieuse'' sustained four killed and eleven wounded.

Later that year ''Imperieuse'' returned to Port Mahon for an extensive refit and while she was undergoing repairs Duncan was offered the command of the frigates HMS ''Resistance'' and HMS ''Undaunted''. However, he decided to remain with ''Imperieuse'' after receiving a letter from the crew expressing their admiration for the captain and their desire for him to remain with the ship. In April 1813 ''Imperieuse'' departed Mahon leading a squadron of three frigates and two brigs to resume the blockade of Naples.

In September the squadron arrived off the Port of Anzio where it discovered a French convoy of 29 merchant vessels protected by two batteries on a

fifth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a fifth rate was the second-smallest class of warships in a hierarchical system of six " ratings" based on size and firepower.

Rating

The rating system in the Royal ...

frigate of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

. Built in Ferrol, Spain, for the Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, ...

she was launched as ''Medea'' in 1797. In 1804 she was part of a squadron carrying gold from South America to Spain that was seized by the British while Spain and Britain were at peace. ''Medea'' was subsequently taken into service with the Royal Navy and was briefly named HMS ''Iphigenia'' before being renamed ''Imperieuse'' in 1805.

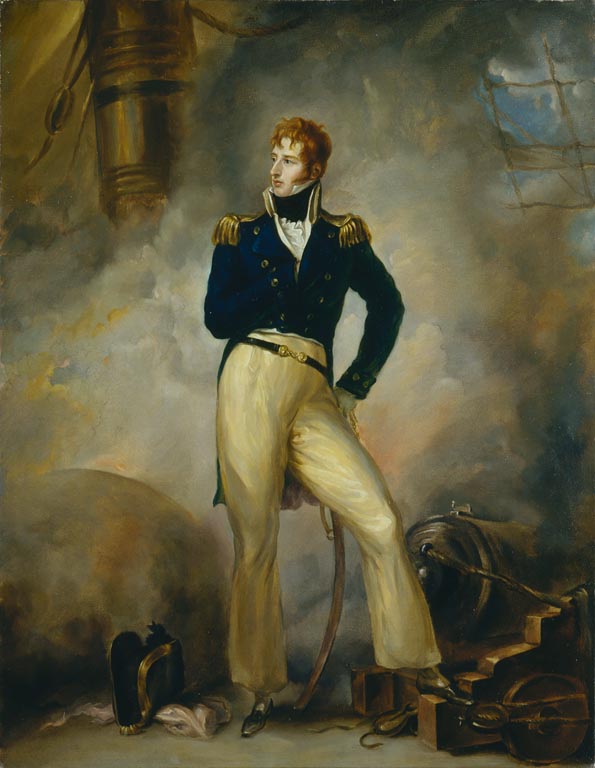

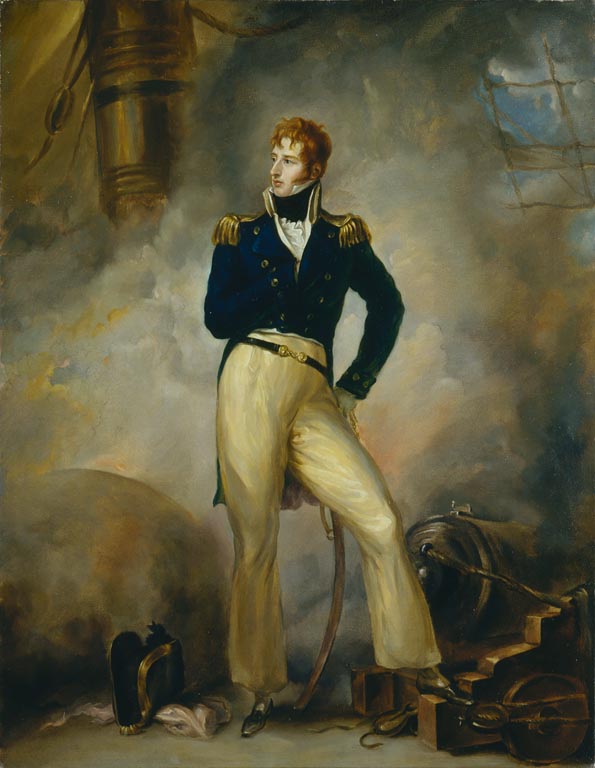

In 1806 command of ''Imperieuse'' was given to Lord Cochrane. She was dispatched to the Mediterranean where she undertook a series of notable exploits, capturing a large number of war prizes and carrying out raids against enemy positions along the French and Spanish coastline. After a brief return to England, ''Imperieuse'' assisted with the attack on the French fleet at Basque Roads in 1809. During the battle she was heavily engaged, assisting with the destruction of four French ships of the line and a frigate. Later that year she took part in the unsuccessful Walcheren Campaign

The Walcheren Campaign ( ) was an unsuccessful British expedition to the Netherlands in 1809 intended to open another front in the Austrian Empire's struggle with France during the War of the Fifth Coalition. Sir John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chath ...

.

In 1811 ''Imperieuse'' returned to the Mediterranean under the command of Henry Duncan Henry Duncan may refer to:

* Henry Duncan (minister) (1774–1846), Scottish minister, geologist and social reformer; founder of the savings bank movement

* Henry Duncan (naval officer, born 1735) (1735–1814), Naval captain and Deputy Comptroller ...

where she was employed along the coast of Italy, operating with success against Neapolitan and French shipping and shore fortifications. She returned to England in 1814 and was paid off

Ship commissioning is the act or ceremony of placing a ship in active service and may be regarded as a particular application of the general concepts and practices of project commissioning. The term is most commonly applied to placing a warship in ...

and placed in ordinary

''In ordinary'' is an English phrase with multiple meanings. In relation to the Royal Household, it indicates that a position is a permanent one. In naval matters, vessels "in ordinary" (from the 17th century) are those out of service for repair o ...

the following year. Converted to a quarantine ship in 1818, she was eventually sold and broken up

Ship-breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships for either a source of Interchangeable parts, parts, which can be sold for re-use, ...

in 1838.

Spanish service

''Medea'' was a 40-gun frigate of theSpanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, ...

designed by Julian Martin de Retamosa. She was launched in Ferrol in November 1797, and was given the religious alias ''Santa Bárbara''. Her dimensions were along the gun deck

The term gun deck used to refer to a deck aboard a ship that was primarily used for the mounting of cannon to be fired in broadsides. The term is generally applied to decks enclosed under a roof; smaller and unrated vessels carried their guns ...

, at the keel, with a beam of and a depth in the hold of . This made her 1,045 tons burthen

Builder's Old Measurement (BOM, bm, OM, and o.m.) is the method used in England from approximately 1650 to 1849 for calculating the cargo capacity of a ship. It is a volumetric measurement of cubic capacity. It estimated the tonnage of a ship bas ...

(bm).

Battle of Cape Santa Maria

In August 1804, ''Medea'' was commanded by Capitán Francisco de Piedrola y Verdugo when she departed Montevideo for Cadiz. She was accompanied by the frigates '' Fama'', ''Mercedes'' and ''Santa Clara'' and carried Rear Admiral José de Bustamante y Guerra who assumed overall command of the squadron. Receiving intelligence the Spanish ships were laden with treasure that was to be used to bolster Spanish finances prior to a declaration of war against Great Britain, the Royal Navy sent a squadron of four frigates to seize the Spanish ships and their cargo. The British intercepted the Spanish squadron off the southern coast of Portugal on 5 October and demanded their surrender but Bustamante refused. HMS ''Indefatigable'', the British flagship commanded by Captain Graham Moore, fired a warning shot across ''Medea''s bow and a general exchange of fire subsequently broke out between the squadrons. After ten minutes ''Mercedes'' was destroyed by an explosion in her magazine and soon after ''Santa Clara'' and ''Medea'', which had been in close action with ''Indefatigable'', both surrendered. ''Fama'' broke away in an attempt to escape but was captured hours later by HMS ''Lively''. ''Medea'' suffered two killed and ten wounded. The capture of the squadron incited outrage in Spain and in December the Spanish King made a formal declaration of war against Britain.British service

The captured ''Medea'' arrived atPlymouth dockyard

His Majesty's Naval Base, Devonport (HMNB Devonport) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Portsmouth) and is the sole nuclear repair and refuelling facility for the Ro ...

in October 1804 and was subsequently taken into service with the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

. She was initially registered as HMS ''Iphigenia'' but renamed HMS ''Imperieuse'' in December 1805. Between February and November 1806 she underwent a large repair at Plymouth. Classed as a 38-gun fifth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a fifth rate was the second-smallest class of warships in a hierarchical system of six " ratings" based on size and firepower.

Rating

The rating system in the Royal ...

, she was given twenty-eight cannon on the upper deck, ten carronades on the quarterdeck and two and two carronades on her forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " be ...

.

Bay of Biscay

On 2 September 1806 Lord Cochrane was commissioned as the captain of ''Imperieuse''. After her repairs were completed in November, ''Imperieuse'' joined a British squadron under Commodore Richard Keats stationed off Basque Roads. Cochrane was given orders to cruise independently of the squadron and captured two prizes off Les Sables d'Olonne on 19 December and another at the entrance of theGaronne

The Garonne (, also , ; Occitan, Catalan, Basque, and es, Garona, ; la, Garumna

or ) is a river of southwest France and northern Spain. It flows from the central Spanish Pyrenees to the Gironde estuary at the French port of Bordeaux – ...

on 31 December. On 7 January 1807 a number of boats from ''Imperieuse'' led by Lieutenant David Mapleton stormed a fort protecting the Arcachon Bay

Arcachon Basin or alternatively Arcachon Bay (French: ''Bassin d'Arcachon'') is a bay of the Atlantic Ocean on the southwest coast of France, situated in Pays de Buch between the Côte d'Argent and the Côte des Landes, in the region of Aquitai ...

destroying its battery

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

of four 36-pounders, two field guns and a 13-inch mortar. Requiring repairs to her rudder, ''Imperieuse'' returned to Plymouth in February 1807.

Mediterranean

After Cochrane was given a leave of absence due to ill-health, Captain Alexander Skene took temporary command of ''Imperieuse'' and she sailed forUshant

Ushant (; br, Eusa, ; french: Ouessant, ) is a French island at the southwestern end of the English Channel which marks the westernmost point of metropolitan France. It belongs to Brittany and, in medieval terms, Léon. In lower tiers of govern ...

to join a blockading fleet off Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

. She returned to Plymouth in August 1807 whereupon Cochrane resumed command and was given orders to escort a convoy of merchant ships to Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

. She arrived at Valletta

Valletta (, mt, il-Belt Valletta, ) is an administrative unit and capital of Malta. Located on the main island, between Marsamxett Harbour to the west and the Grand Harbour to the east, its population within administrative limits in 2014 wa ...

in October and proceeded north to join the Mediterranean Fleet off Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. On 14 November, ''Imperieuse'' encountered an armed polacre

A polacca (or ''polacre'') is a type of seventeenth- to nineteenth-century sailing vessel, similar to the xebec. The name is the feminine of "Polish" in the Italian language. The polacca was frequently seen in the Mediterranean. It had two or th ...

off the coast of Montecristo

Montecristo, also Monte Cristo (, ) and formerly Oglasa ( grc, Ὠγλάσσα, Ōglássa), is an island in the Tyrrhenian Sea and part of the Tuscan Archipelago. Administratively it belongs to the municipality of Portoferraio in the province ...

which Cochrane suspected was a Genoese privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

. After the polacre's captain refused to allow boats from ''Imperieuse'' to investigate the ship, she was captured in a brief but violent boarding action which cost ''Imperieuse'' two killed and 13 wounded, and the privateer one dead and 15 wounded. However, the polacre later proved to be Maltese—a friendly vessel—operating under a letter of marque.

In December 1807, ''Imperieuse'' was given a two-month cruise in the Adriatic and seized three merchant vessels carrying illegal licences to trade. She was subsequently dispatched to the western Mediterranean in February where she sank two

In December 1807, ''Imperieuse'' was given a two-month cruise in the Adriatic and seized three merchant vessels carrying illegal licences to trade. She was subsequently dispatched to the western Mediterranean in February where she sank two gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-ste ...

s and captured a third off the coast of Cartagena, Spain. On 21 February 1808 ''Imperieuse'' launched a surprise attack on a French privateer—''L'Orient''—and two merchant vessels moored under the gun batteries at Almeria. Flying a neutral US flag—a legitimate '' ruse de guerre''—she anchored alongside the privateer before swiftly hoisting her British colours and launching her boats in a cutting out expedition led by Lieutenant Edward Hunt Caulfield. Although the Spanish battery consequently opened fire, all three enemy vessels were taken with little damage. During the boarding action Caulfield was killed by a volley of musketry as he leapt aboard the privateer and 10 others were injured. After bringing her prizes in to Gibraltar, ''Imperieuse'' sailed for the Balearic Islands on 5 March. Patrolling the coasts of Majorca and Menorca, she captured 10 small prizes and bombarded the Spanish army barracks at Ciutadella. She then proceeded to carry out a series of raids along the coast of Catalonia before returning to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

for a refit.

In June 1808, Spain switched allegiance and became an ally of Britain, and Cochrane was subsequently given orders by Vice Admiral Lord Collingwood

Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, 1st Baron Collingwood (26 September 1748 – 7 March 1810) was an admiral of the Royal Navy, notable as a partner with Lord Nelson in several of the British victories of the Napoleonic Wars, and frequently as ...

, Commander of the Mediterranean fleet, to assist Spanish efforts to drive the French garrison out of Barcelona. Arriving at Port Mahon

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

on 16 July, ''Imperieuse'', HMS ''Hind'' and HMS ''Kent'' escorted a convoy of Spanish troops from Majorca to the mainland. Cochrane then proceeded to disrupt the French supply lines sending landing parties ashore to attack the main coastal road between Barcelona and Blanes

Blanes () is a town and municipality in the comarca of Selva in Girona, Catalonia, Spain. During Roman rule it was named Blanda or Blandae. It is known as the "Gateway to the Costa Brava". Its coast is part of the Costa Brava, which stretches ...

and assisted Catalan militia in the capture of a castle at Montgat

Montgat () is a municipality in the ''comarca'' of the Maresme in

Catalonia, Spain. It is situated on the coast between Badalona (Barcelonès) and El Masnou, to the north-east of

Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of nor ...

.

''Imperieuse'' arrived off the mouth of the Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; wae, Rotten ; frp, Rôno ; oc, Ròse ) is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and southeastern France before discharging into the Mediterranean Sea. At Ar ...

on 16 August and proceeded to destroy a string of signal stations and barracks along the French coast. On 7 September, ''Imperieuse'' was joined by HMS ''Spartan'' commanded by Captain Jahleel Brenton

Vice Admiral Sir Jahleel Brenton, 1st Baronet, KCB (22 August 1770 – 21 April 1844) was a British officer in the Royal Navy who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Brenton was born in British America but his family ...

, and continued amphibious operations against the French. At dawn on 10 September, boats from ''Imperieuse'' and ''Spartan'' launched an attack on a series of gun batteries near Port-Vendres. Landing at the southernmost battery, the guns were briskly spiked and barracks blown up. As French troops gathered to respond to the threat, Cochrane and Brenton responded by sending a detachment of boats filled with the ship's boys disguised in the scarlet jackets of the Royal Marines to launch a diversionary attack to the north. Meanwhile, the main assault successfully destroyed the remaining batteries while ''Imperieuse'' anchored close to the shore and drove back an advancing body of cavalry with grapeshot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

. Three days later ''Imperieuse'' and ''Spartan'' captured five merchant vessels and ''Spartan'' subsequently returned to port with the prizes while ''Imperieuse'' continued with her cruise.

''Imperieuse'' arrived at the Gulf of Roses in November to assist with the defence of Rosas which was under siege

''Under Siege'' is a 1992 American action thriller film directed by Andrew Davis, written by J. F. Lawton, and starring Steven Seagal as a former Navy SEAL who must stop a group of mercenaries, led by Tommy Lee Jones, after they commandeer the ...

by some 12,000 French and Italian troops under General Honoré Charles Reille. Situated on the coastal road linking France to Barcelona, the town was flanked by a citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

I ...

and a fort built on a promontory near the coast. Although a breach had been created by French cannon on high ground to the east, Cochrane assumed command of the fort and brought over two-thirds of his crew ashore to lay booby traps and bolster its defences. After gaining possession of the town the French launched an assault on the fort on 30 November which was repulsed with heavy losses inflicted on the attackers. However, on 5 December, the Spanish garrison in the citadel surrendered and Cochrane found his position in the fort untenable. Covered by the ''Imperieuse''s guns, Cochrane and his men returned to their ship and set off demolition charges which partially destroyed the fort. Continuing northward along the Catalonian coast ''Imperieuse'' sighted a convoy of French merchant vessels moored near Cadaqués. Cochrane brought ''Imperieuse'' inshore and captured eleven vessels laden with supplies for the French army and the convoy's escorts—a 7-gun cutter and 5-gun lugger

A lugger is a sailing vessel defined by its rig, using the lug sail on all of its one or several masts. They were widely used as working craft, particularly off the coasts of France, England, Ireland and Scotland. Luggers varied extensively ...

.

Battle of Basque Roads

''Imperieuse'' returned to Plymouth on 19 March 1809 and was ordered to depart again just 10 days later to join Admiral Lord Gambier's blockading squadron at Basque Roads, France. A French fleet lay at anchor in the narrow roadstead and the British Admiralty sought to destroy it by means of a

''Imperieuse'' returned to Plymouth on 19 March 1809 and was ordered to depart again just 10 days later to join Admiral Lord Gambier's blockading squadron at Basque Roads, France. A French fleet lay at anchor in the narrow roadstead and the British Admiralty sought to destroy it by means of a fire ship

A fire ship or fireship, used in the days of wooden rowed or sailing ships, was a ship filled with combustibles, or gunpowder deliberately set on fire and steered (or, when possible, allowed to drift) into an enemy fleet, in order to destroy sh ...

attack planned and executed by Cochrane. Arriving at Basque Roads on 3 April Cochrane took ''Imperieuse'' inshore to reconnoitre the French position and began preparations for an assault against the eleven French ships of the line and two frigates anchored in a narrow channel under the batteries of the Île-d'Aix

Île-d'Aix () is a commune and an island in the Charente-Maritime department, region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine (before 2015: Poitou-Charentes), off the west coast of France. It occupies the territory of the small Isle of Aix (''île d'Aix''), in the ...

. On 11 April, three explosion vessels and 20 fire ships were launched against the French position while ''Imperieuse'', , , and took up position north of the anchorage to receive the crews returning from the fire ships. Although the fire ships inflicted only minor damage, all but two French vessels ran aground in the estuary of the river Charente while attempting to escape the threat.

''Imperieuse'' was the closest British ship to the anchorage and the first to observe the grounded French fleet at dawn the following day. Cochrane was eager to follow up the attack and spent the morning issuing a frantic series of signals to Gambier imploring him to dispatch the British fleet which were ignored. As a consequence Cochrane allowed ''Imperieuse'' to slowly drift towards the French ships and made a final signal which he believed Gambier could not overlook: "The ship is in distress and requires to be assisted immediately". ''Imperieuse'' subsequently brought her starboard broadside to bear upon , ''Aquilon'', and ''Ville de Varsovie'', and opened fire, inflicting severe damage upon the ''Calcutta''s hull. Gambier reluctantly dispatched a squadron of British ships to support ''Imperieuse'' prompting the demoralised crew of the ''Calcutta'' to abandon ship. Cochrane sent boats to take possession of her but the vessel was mistakenly set on fire and destroyed. The British reinforcements formed a line of battle

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

and opened fire, forcing the surrender of two ships of the line and the scuttling of another. During the engagement ''Imperieuse'' suffered extensive damage to her masts, rigging and sails in addition to three dead and eleven wounded.

The British ships were ordered to return to the main fleet in Basque Roads at dawn the following day but ''Imperieuse'' remained—Cochrane argued the orders only applied to his reinforcements—and she was joined by ''Pallas'', , , and eight other smaller ships. Cochrane ordered a renewed attack on the remaining grounded ships but it had little effect. On the morning of 14 April Gambier directed a signal of recall to the ''Imperieuse'' and the next day she was ordered back to England with Gambier's dispatches.

Walcheren Campaign

After creating a scandal by publicly denouncing Gambier's conduct at Basque Roads, Cochrane's naval career was ruined and he turned his attention to politics. In June 1809 command of ''Imperieuse'' passed to Captain Thomas Garth who set sail from the Downs on 30 July with a large British fleet bound for the Netherlands. The fleet formed part of the unsuccessful Walcheren Campaign – a joint expedition with the army that aimed to destroy French dockyards atFlushing

Flushing may refer to:

Places

* Flushing, Cornwall, a village in the United Kingdom

* Flushing, Queens, New York City

** Flushing Bay, a bay off the north shore of Queens

** Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), a community in Queens

** Flushin ...

and Antwerp. While ascending the River Scheldt on 16 August, ''Imperieuse'' mistakenly entered a channel which took her within range of a fort at Terneuzen. During an exchange of cannonade ''Imperieuse'' discharged a number of shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard o ...

s from her carronades, one of which exploded in the fort's magazine. This caused some 3,000 barrels of gunpowder to explode, killing 75 men of the fort's garrison.

Return to the Mediterranean

On 22 September 1810, CaptainHenry Duncan Henry Duncan may refer to:

* Henry Duncan (minister) (1774–1846), Scottish minister, geologist and social reformer; founder of the savings bank movement

* Henry Duncan (naval officer, born 1735) (1735–1814), Naval captain and Deputy Comptroller ...

assumed command of ''Imperieuse'' in Gibraltar and in June the following year she was dispatched to the Mediterranean to join the Royal Navy's blockading fleet off Toulon. The commander of the fleet, Sir Edward Pellew, gave ''Imperieuse'' orders to patrol the coast of Naples and on 11 October Duncan discovered three gunboats moored under a fort at Positano

Positano (Campanian: ) is a village and ''comune'' on the Amalfi Coast (Province of Salerno), in Campania, Italy, mainly in an enclave in the hills leading down to the coast.

Climate

The climate of Positano is very mild, of the Mediterranean ...

. Boats from ''Imperieuse'' under the command of Lieutenant Eaton Stannard Travers were sent to silence the fort. Despite coming under heavy musket fire, the British sailors drove out the fort's defenders and destroyed the battery before returning to their boats and capturing two of the gunboats. During the attack one marine was killed and two crewmen injured while ''Imperieuse'', which had come under heavy fire from the fort, had her foretopsail yard

The yard (symbol: yd) is an English unit of length in both the British imperial and US customary systems of measurement equalling 3 feet or 36 inches. Since 1959 it has been by international agreement standardized as exactly ...

shot away.

''Imperieuse'' was subsequently joined by the 32-gun frigate HMS ''Thames'' commanded by Captain Charles Napier. On 19 October, they anchored near Palinuro

Palinuro is an Italian small town, the most populated civil parish (''frazione'') of Centola, Province of Salerno, in the Campania region. The name of the town is derived from Palinurus, the helmsman of Aeneas, as recorded in the fifth and sixt ...

and dispatched their boats to the shore, capturing 10 armed polacres laden with oil.Clowes (1900), p. 494.Woodman (2001), p. 168. Two days later they discovered 10 Neapolitan gunboats and several merchant vessels moored under a fort in the port at Palinuro. Deeming their numbers insufficient to attack the port, Duncan dispatched ''Thames'' to British-occupied Sicily to request reinforcements and on 28 October she returned with 250 men of the 62nd Regiment of Foot. On 1 November the infantry and a party of marines and sailors launched their attack, capturing the high ground overlooking the harbour. The following morning ''Imperieuse'' and ''Thames'' bore down on the port and ran along within close range of the gunboats while discharging their broadsides, sinking two of the vessels and forcing the surrender of the others. They then anchored close to the fort and commenced a brisk cannonade that forced the fort to surrender within 30 minutes. Over the next two days the fort was blown up and once the troops re-embarked the two frigates departed with six gunboats and 22 felucca

A felucca ( ar, فلوكة, falawaka, possibly originally from Greek , ) is a traditional wooden sailing boat used in the eastern Mediterranean—including around Malta and Tunisia—in Egypt and Sudan (particularly along the Nile and in protect ...

s and 20 large spars.

In June 1812, ''Imperieuse'' was part of a squadron commanded by Captain Patrick Campbell of the 74-gun ship of the line HMS ''Leviathan'' patrolling the western coast of Italy. On 27 June, the squadron launched boats to attack a convoy of 18 French vessels anchored off Alassio and Laigueglia. Although the British destroyed two batteries on the shore, they encountered heavy resistance from the French defenders. Attempts to bring off the French vessels were abandoned and they were instead destroyed by the British guns. While carrying out the expedition ''Imperieuse'' sustained four killed and eleven wounded.

Later that year ''Imperieuse'' returned to Port Mahon for an extensive refit and while she was undergoing repairs Duncan was offered the command of the frigates HMS ''Resistance'' and HMS ''Undaunted''. However, he decided to remain with ''Imperieuse'' after receiving a letter from the crew expressing their admiration for the captain and their desire for him to remain with the ship. In April 1813 ''Imperieuse'' departed Mahon leading a squadron of three frigates and two brigs to resume the blockade of Naples.

In September the squadron arrived off the Port of Anzio where it discovered a French convoy of 29 merchant vessels protected by two batteries on a

In June 1812, ''Imperieuse'' was part of a squadron commanded by Captain Patrick Campbell of the 74-gun ship of the line HMS ''Leviathan'' patrolling the western coast of Italy. On 27 June, the squadron launched boats to attack a convoy of 18 French vessels anchored off Alassio and Laigueglia. Although the British destroyed two batteries on the shore, they encountered heavy resistance from the French defenders. Attempts to bring off the French vessels were abandoned and they were instead destroyed by the British guns. While carrying out the expedition ''Imperieuse'' sustained four killed and eleven wounded.

Later that year ''Imperieuse'' returned to Port Mahon for an extensive refit and while she was undergoing repairs Duncan was offered the command of the frigates HMS ''Resistance'' and HMS ''Undaunted''. However, he decided to remain with ''Imperieuse'' after receiving a letter from the crew expressing their admiration for the captain and their desire for him to remain with the ship. In April 1813 ''Imperieuse'' departed Mahon leading a squadron of three frigates and two brigs to resume the blockade of Naples.

In September the squadron arrived off the Port of Anzio where it discovered a French convoy of 29 merchant vessels protected by two batteries on a mole

Mole (or Molé) may refer to:

Animals

* Mole (animal) or "true mole", mammals in the family Talpidae, found in Eurasia and North America

* Golden moles, southern African mammals in the family Chrysochloridae, similar to but unrelated to Talpida ...

, a tower to the north and another battery covering the mole to the south. The squadron was reinforced by the 74-gun HMS ''Edinburgh'' under Captain George Dundas George Dundas may refer to:

* George Dundas (1690–1762), MP for Linlithgowshire 1722–1727 and 1741–1743

* George Dundas (Royal Navy officer) (1778–1834), Royal Navy admiral and member of parliament for Richmond, and for Orkney & Shetland

* ...

on 5 October and an attack on the port was launched that same day. ''Imperieuse'' and ''Resistance'' took up position opposite the mole, HMS ''Swallow'' anchored near the tower while HMS ''Eclair'', HMS ''Pylades'' and ''Edinburgh'' took station alongside the covering battery. After opening fire, a landing party led by Lieutenant Travers captured the southern battery while another of ''Imperieuse''s officers, Lieutenant Mapleton, led a party that took possession of the mole. The batteries were subsequently blown up by the British and the entire convoy was captured without any losses sustained by the attackers.Clowes (1900), p. 535.

Fate

After theTreaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

and the end of hostilities with France, ''Imperieuse'' returned to England in July 1814 and upon arrival Duncan was appointed to the newly built fifth-rate frigate HMS ''Glasgow''. ''Imperieuse'' briefly came under the command of Captain Philip Dumaresq and Captain Joseph James before she was paid off

Ship commissioning is the act or ceremony of placing a ship in active service and may be regarded as a particular application of the general concepts and practices of project commissioning. The term is most commonly applied to placing a warship in ...

and placed in ordinary

''In ordinary'' is an English phrase with multiple meanings. In relation to the Royal Household, it indicates that a position is a permanent one. In naval matters, vessels "in ordinary" (from the 17th century) are those out of service for repair o ...

at Sheerness in 1815. In 1818 she was converted to a lazarette

The lazarette (also spelled lazaret) of a boat is an area near or aft of the cockpit. The word is similar to and probably derived from lazaretto. A lazarette is usually a storage locker used for gear or equipment a sailor or boatswain would us ...

(quarantine ship) and moved to Stangate Creek in the estuary of the River Medway. In September 1838, she was sold at Sheerness for £1,705 and subsequently broken up

Ship-breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships for either a source of Interchangeable parts, parts, which can be sold for re-use, ...

at Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe () is a district of south-east London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, as well as the Isle of D ...

.

Citations

References

* * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Imperieuse (1805), HMS 1797 ships Ships built in Ferrol, Spain Captured ships Fifth-rate frigates of the Royal Navy Frigates of the Spanish Navy